If I were a fashion designer, the clothes would be all about what's on the inside. Beautiful silk linings. Colorful finishes on the seams. Wild patterns on the inside of the collar, the placket. Brocade interiors showing when you rolled up the shirt or trouser cuffs.

Then the ads could all be about getting undressed. Unbuttoning, wriggling out of the pants. The ads would be as much fun as the clothes.

But I can't even sew. I wish someone would do this.

Monday, October 18, 2010

Monday, March 16, 2009

THE TELEMARKETER'S POINT OF VIEW

I like it best when we work at the two phones in the lunch alcove, just Hank and me. It's crowded, rubbing up against the fax machine, the copier and the lunch table. But there's a huge window with this dramatic western panorama. We see thunderstorms; we see sunsets. We might be lowly phoners, but we've got a better view than most CEO's.

Our office faces the Cook County Jail. Behind it and a little to its left is the Stock Exchange. Hank jokes they should build an airbridge from the jail to the Exchange, like they've got in Minneapolis, to avoid trudging through the snow. But he's not thinking about weather. He wants to give the inmates a shot at sabotaging the markets, or make the traders spend the night in a cell. Maybe both.

The jail's a funny building, not prison-like at all. It's a high-rise, covered with skinny rectangular slits instead of windows. It's a big triangular block on end -- not like any place I've ever seen. Seems they couldn't bother with a fourth wall for the trouble locked inside.

Down at the base, there's this small grove of sickly locust trees in concrete planters. Listless trees, Hank calls them. Half the locusts have signs nailed to their trunks warning: No Skateboarding, No Roller Blading Allowed. Sometimes the phoners sit there, in Prisoner Plaza, and we smoke or eat a taco. We watch the guards and visitors slip in and out of the lobby. Nobody's ever smiling.

Out on the sidewalk one day, I overheard a tour guide say the jail was designed by some guy called Stanley Tigerman, which sounds like a made up name to me. Anyway, what's most interesting about the jail, you can't tell from the ground. It's only visible from up here, on the 13th floor of the Old Colony Building. You can't see much of the roof level prison yard through the bars - just a bunch of faceless bodies milling around in orange jumpsuits. But we've got a bird's eye view of the action on top of the parking lot north of the jail and across the el tracks. It's kitty corner from our big window. Every week or so, somebody spills out of a car - a fat mamasita dragging herself out of a beat up Ford, or a whole family pouring out of a new van. They've always got a clutch of melamine balloons, and they're always waving like mad up at the prison roof. Sometimes the kids are jumping up and down. Once, two girls unfurled a long orange banner that read Happy Birthday Calvert.

On the day I'm talking about, we were phoning into a western suburb. It was still light out, barely, and there was a faint pink glow dusting the horizon. Hank and I staked out our window seats and looked around. Thirteen floors below, someone had tossed a perfectly good motorcycle into a trash dumpster outside the jail, like an aborted escape attempt.

I sat and shuffled my call sheets. The office was droning like a hornet's nest. The air itself seemed infected with our murmured questions, "If the election were today, would you vote for..."

Then, Hank and I heard this hooting and hollering from across the way - even through the thick, hundred year old panes of glass. Prisoners were yelping and whistling. It sounded like a riot. I thought that maybe the inmates were in revolt. I pictured them, bands of orange men, streaming through Prisoner Plaza, playing hide and seek in the locust trees, smiles of glee plastered across their faces.

Hank nodded at the parking structure. On the roof, there was a tall black girl, wearing this silver sequined bathing suit and spiked heels. She was strutting back and forth in front of her car, a shiny Red Jeep Cherokee. She'd stop and wiggle her hips or lift her breasts up toward the prison roof with her hands. She did this quite a while before breaking her rhythm and opening the car door. She left it ajar and ducked behind it, bending away from the crowd. Then we watched her hand peek over the top like a shy puppet before tossing her silver bra off the parking lot roof. It landed on the el tracks. The hooting got louder. Then, nothing. No girl. It was just a few seconds, but it felt like forever. She was hiding, or waiting maybe, or trying to work up her nerve. When she finally stood up and slammed the door, she planted her legs wide apart and propped her hands on her hips like she was some kind of superhero nudist, without the cape.

But nobody was thinking about her superpowers. She had the largest naked breasts I'd ever seen, not that I've seen that many. I never saw my momma undressed and my roommate Caroline is pretty modest, whenever she's around.

Hank nudged me and slid his chair closer to mine. "She's got a great tan," he said. He tapped my hand with the tip of his finger and I felt my throat catch. I must have been holding my breath. Maybe he was excited. I mean, I was excited. I wanted to watch. And I'm not attracted to women, at least as far as I know.

The inmates went wild. The girl started swaying and then shimmying, and then shaking side to side. Her nipples were huge and dark, nearly black in the twilight.

I don't know if she didn't hear it above the prisoners' thundering feet and hands. Or maybe she just didn't care when the parking security car drove up the ramp behind her. Instead of turning around, she dropped her head back and threw her arms into the air, like she'd just walked a tightrope, ta da!

That's when our supervisor Marva hustled in and dropped the blinds. "Show's over," she barked. "Back to work."

We had a deadline. Otherwise, I'm not sure she'd have cared.

So I found my place on the list of randomly selected phone numbers. As I dialed the next household, I could still hear the yowling and stomping. Somewhere in the distance there was a siren. The screech of the next train grew louder as it rounded the bend from Wabash, heading west onto Van Buren. Just about the time I launched into my next poll, the front car was barreling along the tracks, passing the parking lot and chewing up the silver sequined bra dangling over the rails.

(originally published in the Salt River Review, James Cervantes, editor)

Thursday, December 04, 2008

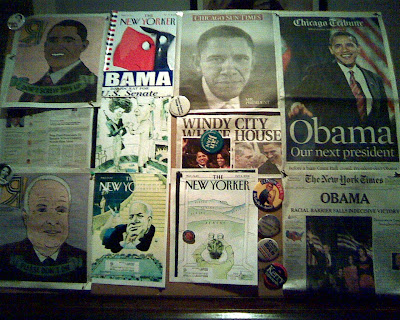

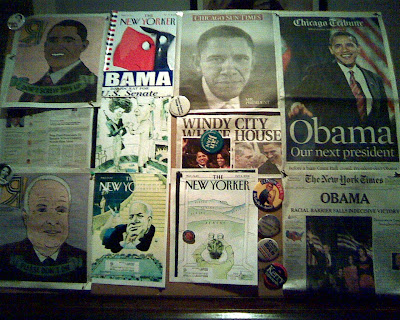

FORGETTING OBAMA

MEMORY ALMOST FULL

I've always been a terrible judge of character. I can't even remember the first time I may have spoken to Barack Obama. Yet today I was flipping through the bulky old Rolodex I saved from my last job (before I had a blackberry) and I came across his name. It was printed in my hand (mostly caps) and in the blue ink that I prefer. I had his phone number, and his fax. His name was misspelled: Barak. I didn't favor him with any title. Was he not yet a Senator? Did I harbor a grudge because of my friendship with Alice Palmer?

I couldn't resist dialing -- rather, tapping in -- the number. It rang. A woman on the other end rattled off a name. Excuse me? I said. No, it wasn't the transition office, or his U.S. Senate office, or even a recycled Illinois state Senate number. It was a law firm, Judd Miner's place. Harold Washington's former corporation counsel, a man who had once offered me a job. I accepted it, and then changed my mind. I send him a box of Godiva chocolates, embarrassed at my change of heart.

Why had I called Obama there? What might I have called about -- or faxed to him? I didn't have his business card, so I must have sent something in response to a call, a personal request.

I told the receptionist I had the wrong number and returned the receiver to its cradle. I corrected the president-elect's spelling, printing a "c" above a little carrot pointed between the "a" and the 'k." I left the card behind the divider labeled "O" and returned to my alphabetical excavation, searching for the Anne Spillane.

My life dissolves as I walk through it.

I've always been a terrible judge of character. I can't even remember the first time I may have spoken to Barack Obama. Yet today I was flipping through the bulky old Rolodex I saved from my last job (before I had a blackberry) and I came across his name. It was printed in my hand (mostly caps) and in the blue ink that I prefer. I had his phone number, and his fax. His name was misspelled: Barak. I didn't favor him with any title. Was he not yet a Senator? Did I harbor a grudge because of my friendship with Alice Palmer?

I couldn't resist dialing -- rather, tapping in -- the number. It rang. A woman on the other end rattled off a name. Excuse me? I said. No, it wasn't the transition office, or his U.S. Senate office, or even a recycled Illinois state Senate number. It was a law firm, Judd Miner's place. Harold Washington's former corporation counsel, a man who had once offered me a job. I accepted it, and then changed my mind. I send him a box of Godiva chocolates, embarrassed at my change of heart.

Why had I called Obama there? What might I have called about -- or faxed to him? I didn't have his business card, so I must have sent something in response to a call, a personal request.

I told the receptionist I had the wrong number and returned the receiver to its cradle. I corrected the president-elect's spelling, printing a "c" above a little carrot pointed between the "a" and the 'k." I left the card behind the divider labeled "O" and returned to my alphabetical excavation, searching for the Anne Spillane.

My life dissolves as I walk through it.

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

Signs and Wonders

First thing today, a bird fell out of the sky at my feet. I was walking north on Dearborn Street and a pretty feathered olive green thing dropped to the sidewalk in front of me, its white legs askew.  It was not as dramatic as having a cougar cross my path, as one crossed my assistant’s a few weeks back, but birds don’t fall before me every day, either.

It was not as dramatic as having a cougar cross my path, as one crossed my assistant’s a few weeks back, but birds don’t fall before me every day, either.

I stared at it a moment—baffled at what to do—and then picked it up between an old receipt and a train schedule. I had no idea if it was dead or alive. A hardened-looking blonde woman stopped and suggested I put it in one of the planters on the street, so “it could be in nature.” I laid it down under a fat, sprouting hosta leaf in one of the city’s planter beds, and rode the elevator up to my office.

At my desk, I googled ‘injured bird Chicago’ and right away a phone number for Chicago Bird Collision Monitors popped up. I was only mildly surprised since Arthur Pearson from my writing group wrote a youth novel about bird rescuers at the John Hancock building.

The CBCM has an emergency hotline, and a network of volunteers who retrieve birds who get injured flying through the Loop; one rescuer works in City Hall, just down the block. The operator said to place the bird in a box or a paper bag. So I found a stray Levenger bag (thrown under my desk with about 7 pairs of shoes).

The CBCM has an emergency hotline, and a network of volunteers who retrieve birds who get injured flying through the Loop; one rescuer works in City Hall, just down the block. The operator said to place the bird in a box or a paper bag. So I found a stray Levenger bag (thrown under my desk with about 7 pairs of shoes).

I went back downstairs with my deputy and we scooped up the bird (a warbler? A finch?) and tucked her into the bag. It was hard to tell if she was still alive—her tiny black bead of an eye was open, rimmed with delicate white feathers. We toted her upstairs, stapled the bag shut and waited for the volunteer.

An hour passed and nobody rang. So I called the hotline again, and the operator located a second rescuer. She couldn’t leave her office, but I offered to bring her the bird. I picked up my little olive green bag with the little olive green bird inside, and set out for the corner of Monroe and Franklin, about a half-mile away. A few blocks later I realized I’d been swinging the bag by its string handles. Yikes! I apologized to the bird and clutched the sack at its top.

About 10 minutes later I reached the ATT lobby and called “Barb” from my cell phone. She said “I’ll be wearing a grey shirt” as if I was making a surreptitious drug delivery. She came down and quickly retrieved the bag without opening it. She’s learned to keep the bags closed; she’s had birds escape, and it’s problematic if they fly around indoors. She shook her head knowingly, then disappeared behind the security turnstile protecting the elevator banks.

That was that. I don’t know if the bird is dead or alive, and I would rather not know. If it’s alive they will give it medical attention. If it’s dead, they’ll note where it was found, and put it to rest. Either way, I’d like them to identify it for me—I couldn’t determine anything from the web, though it looks somewhat like an orange-crowned warbler without the crown. Sadly, deposed.

It was not as dramatic as having a cougar cross my path, as one crossed my assistant’s a few weeks back, but birds don’t fall before me every day, either.

It was not as dramatic as having a cougar cross my path, as one crossed my assistant’s a few weeks back, but birds don’t fall before me every day, either.I stared at it a moment—baffled at what to do—and then picked it up between an old receipt and a train schedule. I had no idea if it was dead or alive. A hardened-looking blonde woman stopped and suggested I put it in one of the planters on the street, so “it could be in nature.” I laid it down under a fat, sprouting hosta leaf in one of the city’s planter beds, and rode the elevator up to my office.

At my desk, I googled ‘injured bird Chicago’ and right away a phone number for Chicago Bird Collision Monitors popped up. I was only mildly surprised since Arthur Pearson from my writing group wrote a youth novel about bird rescuers at the John Hancock building.

The CBCM has an emergency hotline, and a network of volunteers who retrieve birds who get injured flying through the Loop; one rescuer works in City Hall, just down the block. The operator said to place the bird in a box or a paper bag. So I found a stray Levenger bag (thrown under my desk with about 7 pairs of shoes).

The CBCM has an emergency hotline, and a network of volunteers who retrieve birds who get injured flying through the Loop; one rescuer works in City Hall, just down the block. The operator said to place the bird in a box or a paper bag. So I found a stray Levenger bag (thrown under my desk with about 7 pairs of shoes).I went back downstairs with my deputy and we scooped up the bird (a warbler? A finch?) and tucked her into the bag. It was hard to tell if she was still alive—her tiny black bead of an eye was open, rimmed with delicate white feathers. We toted her upstairs, stapled the bag shut and waited for the volunteer.

An hour passed and nobody rang. So I called the hotline again, and the operator located a second rescuer. She couldn’t leave her office, but I offered to bring her the bird. I picked up my little olive green bag with the little olive green bird inside, and set out for the corner of Monroe and Franklin, about a half-mile away. A few blocks later I realized I’d been swinging the bag by its string handles. Yikes! I apologized to the bird and clutched the sack at its top.

About 10 minutes later I reached the ATT lobby and called “Barb” from my cell phone. She said “I’ll be wearing a grey shirt” as if I was making a surreptitious drug delivery. She came down and quickly retrieved the bag without opening it. She’s learned to keep the bags closed; she’s had birds escape, and it’s problematic if they fly around indoors. She shook her head knowingly, then disappeared behind the security turnstile protecting the elevator banks.

That was that. I don’t know if the bird is dead or alive, and I would rather not know. If it’s alive they will give it medical attention. If it’s dead, they’ll note where it was found, and put it to rest. Either way, I’d like them to identify it for me—I couldn’t determine anything from the web, though it looks somewhat like an orange-crowned warbler without the crown. Sadly, deposed.

Tuesday, May 06, 2008

Letting the Blister Rise

This week, Susan Henderson asks LITPARK devotees about what's in their drawers or pockets. In my pocket was an email, with the address of the Israeli consulate, and this is why:

If you’ve ever been to Israel, one of the first things you saw when you landed was a larger-than-life bronze bust of David Ben-Gurion sculpted by my Aunt. Dorothy Wolf. It greeted me when I visited at 17. My son and his friends saw it when they debarked during an 8th grade trip. My Irish researcher, who married a Holocaust survivor’s daughter, saw it there, at Lod Airport.

Today, two days short of the 60th anniversary of the Jewish state, I met my family at the Israeli consulate to dedicate the original cast, a gift from my aunt’s family. I submitted my passport number in advance, took a taxi to Wacker Drive, checked in with my driver’s license at the security desk, rode the restricted elevator and pressed the buzzer beside the locked steel doors.

They gave me a pass on the metal detector, and I joined the crowd.

Aunt Dorothy was there, and thrilled to see me. In truth, every time she saw me she was ecstatic, and gave me a warm embrace: when I walked into the room, 2 minutes later, and 2 minutes after that. Each time was the first time—or so it seemed through her Alzheimer’s fog.

Still, she celebrated. The Israeli Consul-General spoke a moving speech. My father fumbled with his new digital camera as the consulate unveiled a plaque commemorating the occasion. Dorothy blinked, perhaps uncertain about the fuss. It hurt my heart to think about waiting so long for recognition, to the point where it is unrecognizable.

We repaired to a conference room for cookies and wine. Dorothy’s grandchildren were careful to not speak to their father.

My father spoke to me. “You look terrific,” he kvelled. I had done nothing to earn this fawning, save scrub my face and keep mustard off my shirt.

I talked to my taut and pretty girl cousins--talented artists both--in their fashionable black leathers, and they talked back.

There were words I expected and words unexpected:

“Have you ever slept with a black man?”

“I never really noticed this sculpture. I wonder if my children notice my paintings.”

“My husband takes propecia, and his wanger still wangs.”

All this, while my parents argued, just steps away. My father reached for my mother’s hands, and she growled and snapped, more wolf-like with age. I asked them what I always ask, would they please fight later. They tried, and failed, and tried again. And when they left in the elevator, I hid in the bathroom. Not a terrorist or intruder, just a refugee from a Jewish family—safe behind the barriers of windowless steel doors and restricted elevators.

I lagged behind. I skipped the limo and lunch in the suburbs, opting instead for a long, slow stroll on a sunny day. I turned away from them, taking the long-cut through the old library, letting a blister rise on the outside of my foot.

There was a crowd in the large hall on the first floor of the Cultural Center, with retirees, students and lunching lawyers filtering in. A performance was set to begin. I limped happily to a seat. In the center of the room, two men perched on chairs, hugging their guitars. A middle aged white man, and an old black man named Honeyboy Edwards. A guitar legend, or so said the bald human rights lawyer who sat beside me, grinning and describing his work resettling Chinese laborers whose 18th century farms were flooded by 21st century dams. I worked to ignore him while Honeyboy launched into his blues. He strummed, he plucked; he belted out lyrics. Yet nothing but a weak vibration flew from his fingers, a hoarse mumble from his throat. He may be an icon, but he’s not much of a performer anymore. The lunch crowd clapped along, enthralled with his songs. But to me, he was too like Aunt Dorothy, his vitality as shriveled as an old peeled apple.

At a break, I slipped away from the human rights lawyer, before he could ask my name. It was two blocks to my office. With every step I took further from the music, from the consulate, from my family, the blister kept rising--tinting my relief with pain.

The light went yellow at the corner. The traffic cop plugged her lips with a whistle and I picked up my pace.

If you’ve ever been to Israel, one of the first things you saw when you landed was a larger-than-life bronze bust of David Ben-Gurion sculpted by my Aunt. Dorothy Wolf. It greeted me when I visited at 17. My son and his friends saw it when they debarked during an 8th grade trip. My Irish researcher, who married a Holocaust survivor’s daughter, saw it there, at Lod Airport.

Today, two days short of the 60th anniversary of the Jewish state, I met my family at the Israeli consulate to dedicate the original cast, a gift from my aunt’s family. I submitted my passport number in advance, took a taxi to Wacker Drive, checked in with my driver’s license at the security desk, rode the restricted elevator and pressed the buzzer beside the locked steel doors.

They gave me a pass on the metal detector, and I joined the crowd.

Aunt Dorothy was there, and thrilled to see me. In truth, every time she saw me she was ecstatic, and gave me a warm embrace: when I walked into the room, 2 minutes later, and 2 minutes after that. Each time was the first time—or so it seemed through her Alzheimer’s fog.

Still, she celebrated. The Israeli Consul-General spoke a moving speech. My father fumbled with his new digital camera as the consulate unveiled a plaque commemorating the occasion. Dorothy blinked, perhaps uncertain about the fuss. It hurt my heart to think about waiting so long for recognition, to the point where it is unrecognizable.

We repaired to a conference room for cookies and wine. Dorothy’s grandchildren were careful to not speak to their father.

My father spoke to me. “You look terrific,” he kvelled. I had done nothing to earn this fawning, save scrub my face and keep mustard off my shirt.

I talked to my taut and pretty girl cousins--talented artists both--in their fashionable black leathers, and they talked back.

There were words I expected and words unexpected:

“Have you ever slept with a black man?”

“I never really noticed this sculpture. I wonder if my children notice my paintings.”

“My husband takes propecia, and his wanger still wangs.”

All this, while my parents argued, just steps away. My father reached for my mother’s hands, and she growled and snapped, more wolf-like with age. I asked them what I always ask, would they please fight later. They tried, and failed, and tried again. And when they left in the elevator, I hid in the bathroom. Not a terrorist or intruder, just a refugee from a Jewish family—safe behind the barriers of windowless steel doors and restricted elevators.

I lagged behind. I skipped the limo and lunch in the suburbs, opting instead for a long, slow stroll on a sunny day. I turned away from them, taking the long-cut through the old library, letting a blister rise on the outside of my foot.

There was a crowd in the large hall on the first floor of the Cultural Center, with retirees, students and lunching lawyers filtering in. A performance was set to begin. I limped happily to a seat. In the center of the room, two men perched on chairs, hugging their guitars. A middle aged white man, and an old black man named Honeyboy Edwards. A guitar legend, or so said the bald human rights lawyer who sat beside me, grinning and describing his work resettling Chinese laborers whose 18th century farms were flooded by 21st century dams. I worked to ignore him while Honeyboy launched into his blues. He strummed, he plucked; he belted out lyrics. Yet nothing but a weak vibration flew from his fingers, a hoarse mumble from his throat. He may be an icon, but he’s not much of a performer anymore. The lunch crowd clapped along, enthralled with his songs. But to me, he was too like Aunt Dorothy, his vitality as shriveled as an old peeled apple.

At a break, I slipped away from the human rights lawyer, before he could ask my name. It was two blocks to my office. With every step I took further from the music, from the consulate, from my family, the blister kept rising--tinting my relief with pain.

The light went yellow at the corner. The traffic cop plugged her lips with a whistle and I picked up my pace.

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

Too Many Ways to Die

There aren’t so many ways to die before time would take you. There are accidents, diseases, natural disasters and violence.

But there are too many variants of each. A friend’s sister who lost her footing on a mountain-top in Mexico. Cancer in its endless incarnations. Hurricanes in the south and tsunamis in the south Pacific.

As for violence, our species wastes too much creativity on ways to kill. In war, as revenge, for sport, for profit.

This week, on LITPARK, Susan Henderson asks which murders have made an impression on people.

Like everyone, certain murders have haunted me. When I was young it was the little girl who left to buy her mother a greeting card and never made it home alive.

Later, it was Richard Speck’s systematic murder of eight student nurses in one bleak night in the Chicago neighborhood where I used to live. Then it was William Heirens’ serial killings. From the web: Heirens was arrested in 1946 for a number of sex crimes and murders. At one murder scene he scrawled a note in lipstick reading For Heaven's sake catch me before I kill more. I cannot control myself.

I read the book: Catch Me Before I Kill More.

Heirens was long in jail by the time we moved to his town, but his family’s house sat low to the ground three blocks from my own. It was an old-fashioned yellow frame structure, out of place in the brick-y suburb. The house seemed marked, as if he were condemned to be different, an outsider, a criminal—by its very appearance.

One of the most recent murders to affect me—in life, rather than in imagination—was committed by the doctor who lived across the street.

From the news: "On May 23, 2005 a federal jury condemned a Chicago podiatrist to death for murder. Dr. Ronald Mikos fatally shot Joyce Brannon 54, a disabled former nurse, at point-blank range in 2002, just four days before she was to testify against him in a $1 million Medicare fraud case." Brannon lived in the basement of a church, which is where he shot her.

I first got wind of Mikos’ arrest when I came home and saw a number of cruisers and TV vans parked directly across the street.

Mikos was the boyfriend/boarder of a very kindly woman in a tiny beige brick bungalow across from us. Her daughter was friendly with mine, Meredith. Mikos drove a red convertible, and seemed rather innocuous. I would often see him pulling away from the house when I walked the dog. Once, Meredith attended a birthday party at his ex-wife's house in Skokie. I remember large fish tanks. My daughter was quite young, yet I left her there for the afternoon, unattended.

I never knew, until I mentioned the murder to Meredith, that Mikos used to give her and her friend rides home from school in that little red convertible, two innocent grammar school girls, wind whipping through their hair.

They are grown now. My daughter, 18, hiking in Mexico. Her young friend’s family moved far from the home they shared with Mikos.

Yet in my mind’s eye I can see them still, those innocent and trusting grade school girls, doing what I never knew they had done in life: They perch on the back seat of a red 1994 Pontiac convertible. A man who will become a murderer is at the wheel. Their laughter is lost in the wind.

But there are too many variants of each. A friend’s sister who lost her footing on a mountain-top in Mexico. Cancer in its endless incarnations. Hurricanes in the south and tsunamis in the south Pacific.

As for violence, our species wastes too much creativity on ways to kill. In war, as revenge, for sport, for profit.

This week, on LITPARK, Susan Henderson asks which murders have made an impression on people.

Like everyone, certain murders have haunted me. When I was young it was the little girl who left to buy her mother a greeting card and never made it home alive.

Later, it was Richard Speck’s systematic murder of eight student nurses in one bleak night in the Chicago neighborhood where I used to live. Then it was William Heirens’ serial killings. From the web: Heirens was arrested in 1946 for a number of sex crimes and murders. At one murder scene he scrawled a note in lipstick reading For Heaven's sake catch me before I kill more. I cannot control myself.

I read the book: Catch Me Before I Kill More.

Heirens was long in jail by the time we moved to his town, but his family’s house sat low to the ground three blocks from my own. It was an old-fashioned yellow frame structure, out of place in the brick-y suburb. The house seemed marked, as if he were condemned to be different, an outsider, a criminal—by its very appearance.

One of the most recent murders to affect me—in life, rather than in imagination—was committed by the doctor who lived across the street.

From the news: "On May 23, 2005 a federal jury condemned a Chicago podiatrist to death for murder. Dr. Ronald Mikos fatally shot Joyce Brannon 54, a disabled former nurse, at point-blank range in 2002, just four days before she was to testify against him in a $1 million Medicare fraud case." Brannon lived in the basement of a church, which is where he shot her.

I first got wind of Mikos’ arrest when I came home and saw a number of cruisers and TV vans parked directly across the street.

Mikos was the boyfriend/boarder of a very kindly woman in a tiny beige brick bungalow across from us. Her daughter was friendly with mine, Meredith. Mikos drove a red convertible, and seemed rather innocuous. I would often see him pulling away from the house when I walked the dog. Once, Meredith attended a birthday party at his ex-wife's house in Skokie. I remember large fish tanks. My daughter was quite young, yet I left her there for the afternoon, unattended.

I never knew, until I mentioned the murder to Meredith, that Mikos used to give her and her friend rides home from school in that little red convertible, two innocent grammar school girls, wind whipping through their hair.

They are grown now. My daughter, 18, hiking in Mexico. Her young friend’s family moved far from the home they shared with Mikos.

Yet in my mind’s eye I can see them still, those innocent and trusting grade school girls, doing what I never knew they had done in life: They perch on the back seat of a red 1994 Pontiac convertible. A man who will become a murderer is at the wheel. Their laughter is lost in the wind.

Friday, August 17, 2007

LIAM RECTOR

Rest in Peace

BEST FRIEND

Liam Rector

You sailed down

From Provincetown

And I was to meet you

In Key West. I’d never

Sailed. I dressed

In my best and flew

Down from Manhattan,

Where I had been feeling

Punishing failure

And reading Hart Crane.

I brought a robe

I intended to wear

When I jumped off

Our boat mid-sea. I never

Told you that,

Old friend, and I

Apologize now.

What if I had left you mid-ocean

To sail alone?

In our twenty-foot wooden

Thing with no motor

And a radio that didn’t

Work we barely made it

Through the initial storm.

In the Bahamas we

Were often stood

Free beers for being

As insane as we were,

Coming over those waters

With no motor, pure

Sailing like that, a bar

Of soap floating in the cauldron

Of the Bermuda Triangle,

Where motorized cigarette

Boats sped by at money-making

Speeds, running drugs to fill

American needs.

And on our way back

When we lost our rudder

You, former Eagle

Scout, first conscientious

Objector ever to leave

West Point, captain

Of the ski team, jumped

Over the stern

And fashioned out of oar

And thick rope the thing

That would see us to shore

Before we, becalmed,

Drifted off course

100 miles, 100 miles

Of boredom and sun. I snapped

A black and white photo

Of the sea to remind me

Of my boredom, its boredom.

We made it back

To America, hitting

Shore at Boca Raton,

Pulling in midst the boats

Of the very, very rich.

I lived to write this

And never jumped ship.

It was your kinship

Kept me going those years,

Times of ridiculous

Sailing, riotous beers.

Wives sailed by,

So many boats, and you soon

Left for Bangkok and its

Very distant coast.

Being young: being rich

Among inherited ruins.

(AGNI 61)Liam Rector's books of poems are American Prodigal and The Sorrow of Architecture. A book he co-edited with Tree Swenson, On the Poetry of Frank Bidart: Fastening the Voice to the Page, is forthcoming from the University of Michigan Press. Rector directs the graduate Writing Seminars at Bennington College. (4/2005)

Rest in Peace

BEST FRIEND

Liam Rector

You sailed down

From Provincetown

And I was to meet you

In Key West. I’d never

Sailed. I dressed

In my best and flew

Down from Manhattan,

Where I had been feeling

Punishing failure

And reading Hart Crane.

I brought a robe

I intended to wear

When I jumped off

Our boat mid-sea. I never

Told you that,

Old friend, and I

Apologize now.

What if I had left you mid-ocean

To sail alone?

In our twenty-foot wooden

Thing with no motor

And a radio that didn’t

Work we barely made it

Through the initial storm.

In the Bahamas we

Were often stood

Free beers for being

As insane as we were,

Coming over those waters

With no motor, pure

Sailing like that, a bar

Of soap floating in the cauldron

Of the Bermuda Triangle,

Where motorized cigarette

Boats sped by at money-making

Speeds, running drugs to fill

American needs.

And on our way back

When we lost our rudder

You, former Eagle

Scout, first conscientious

Objector ever to leave

West Point, captain

Of the ski team, jumped

Over the stern

And fashioned out of oar

And thick rope the thing

That would see us to shore

Before we, becalmed,

Drifted off course

100 miles, 100 miles

Of boredom and sun. I snapped

A black and white photo

Of the sea to remind me

Of my boredom, its boredom.

We made it back

To America, hitting

Shore at Boca Raton,

Pulling in midst the boats

Of the very, very rich.

I lived to write this

And never jumped ship.

It was your kinship

Kept me going those years,

Times of ridiculous

Sailing, riotous beers.

Wives sailed by,

So many boats, and you soon

Left for Bangkok and its

Very distant coast.

Being young: being rich

Among inherited ruins.

(AGNI 61)Liam Rector's books of poems are American Prodigal and The Sorrow of Architecture. A book he co-edited with Tree Swenson, On the Poetry of Frank Bidart: Fastening the Voice to the Page, is forthcoming from the University of Michigan Press. Rector directs the graduate Writing Seminars at Bennington College. (4/2005)

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

GEOMETRY

I am at the vertex. The endpoint. That is, the intersection of the angle.

Or perhaps I should call it the startpoint, since the two "rays" emanating in splayed directions are of my flesh. My son and daughter both left Evanston yesterday, to different compass points, both literal and figurative.

One traveled east, one northwest, so the hypotenuse of this triangle (were it not obtuse) would cross Lake Michigan like a ferry, taking the watery shortcut to avoid that long drive through Chicago along I-94.

One traveled east, one northwest, so the hypotenuse of this triangle (were it not obtuse) would cross Lake Michigan like a ferry, taking the watery shortcut to avoid that long drive through Chicago along I-94.

But Meredith left by land, at night, in a friend’s parents’ Lexus SUV with a black leather interior for the Ten Thousand Lakes music festival in Detroit Lakes, Minnesota. The irony of driving a luxury vehicle to a faux Woodstock likely didn’t register with her carload of friends, so accustomed are they to comfort. They will camp in the woods, afloat in music and greenery.

But Meredith left by land, at night, in a friend’s parents’ Lexus SUV with a black leather interior for the Ten Thousand Lakes music festival in Detroit Lakes, Minnesota. The irony of driving a luxury vehicle to a faux Woodstock likely didn’t register with her carload of friends, so accustomed are they to comfort. They will camp in the woods, afloat in music and greenery.

I am at the vertex. The endpoint. That is, the intersection of the angle.

Or perhaps I should call it the startpoint, since the two "rays" emanating in splayed directions are of my flesh. My son and daughter both left Evanston yesterday, to different compass points, both literal and figurative.

It’s a shortcut the three of us (plus husband) once took, sailing from Wisconsin to Michigan, letting the wind whip through our hair on the deck of the Badger before debarking for the sandy campsite in Ludington State Park.

Wesley and a friend took a bus east to what once was the city of Detroit, to help a pioneering architect build a house in what once was a neighborhood at Pierce and St. Aubin. It is hardly a city, hardly a neighborhood, anymore. They are erecting what will be the 5th house in two square blocks. Across the street is a whore house. Across the street is a crack hou se. They are different houses. Someone has broken into the shed where they keep their building materials, poisoning the water supply. They are camping in an abandoned apartment building which was filmed for the movie 8 Mile. One of the other squatters claims to have invented Techno Music, and who’s to say he didn’t?

se. They are different houses. Someone has broken into the shed where they keep their building materials, poisoning the water supply. They are camping in an abandoned apartment building which was filmed for the movie 8 Mile. One of the other squatters claims to have invented Techno Music, and who’s to say he didn’t?

Back here in Evanston, kids gone and my husband napping, I have the family computer to myself. I unpack the ipod I got for my birthday. Ipod rhymes with god, and I've noticed that's the way apple treats it in the literature. Never "the" ipod, only "ipod", as if it is omnipotent, not in need of an article to denote specificity. And now that I finally open the box, and inject music into this deity, I know why.

I spend hours worshipping: loading it with the songs that I don’t think my children already have—Gato Barbieri and Eddie Vetter. I drag myself to bed reluctantly, only stopping because the music isn’t free. I sleep deeply until a fury of crashing and scraping rattles me awake. Above my head, roofers are shoveling off the old roof tiles that were nailed there 16 years before, when Meredith was 2 and Wes was 6 and we were rebuilding our house after a fire.

Here at the vertex, I throw on clothes and strap on ipod to walk the dog—the only child remaining at home. We three are in the middle, ipod, dog and me: music and vernal camping to the northwest; techno and urban squatting to the east.

We are the endpoint, or the startpoint. We walk together, the routes I once pushed a stroller. Or rather, I bop to Toad the Wet Sprocket, dog trots and ipod rides my pocket. Later, my children will call me at work. Right now I follow the sidewalks, explore the alleys and register their absence. I scratch the dog's ears and he laps at my hand. Ipod sings and dog pants. It’s an old, sentimental observation: dog is the mirror image of god.

Back here in Evanston, kids gone and my husband napping, I have the family computer to myself. I unpack the ipod I got for my birthday. Ipod rhymes with god, and I've noticed that's the way apple treats it in the literature. Never "the" ipod, only "ipod", as if it is omnipotent, not in need of an article to denote specificity. And now that I finally open the box, and inject music into this deity, I know why.

I spend hours worshipping: loading it with the songs that I don’t think my children already have—Gato Barbieri and Eddie Vetter. I drag myself to bed reluctantly, only stopping because the music isn’t free. I sleep deeply until a fury of crashing and scraping rattles me awake. Above my head, roofers are shoveling off the old roof tiles that were nailed there 16 years before, when Meredith was 2 and Wes was 6 and we were rebuilding our house after a fire.

Here at the vertex, I throw on clothes and strap on ipod to walk the dog—the only child remaining at home. We three are in the middle, ipod, dog and me: music and vernal camping to the northwest; techno and urban squatting to the east.

We are the endpoint, or the startpoint. We walk together, the routes I once pushed a stroller. Or rather, I bop to Toad the Wet Sprocket, dog trots and ipod rides my pocket. Later, my children will call me at work. Right now I follow the sidewalks, explore the alleys and register their absence. I scratch the dog's ears and he laps at my hand. Ipod sings and dog pants. It’s an old, sentimental observation: dog is the mirror image of god.

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

INTERSECTING NAMES, PARALLEL LIVES,

(or a shout-out to my gails...)

Dear Gail and Gail and Gail, etc:

Like you, my name is Gail Siegel.

I happen to be a writer, and every once in a while I google my name to make sure that a story has been published, or to see who is linking to my work. Inevitably, I run across one or another of you other Gail Siegels out there. I get your emails, inviting me to a golf game, or a luncheon in New York. I politely decline.

This is not a new problem. Decades ago, in college, Gail Anne Siegel’s grandmother called me one night. I knew it was a grandmother, but she didn’t sound like my grandmother. She seemed a kindly old woman, and I trust she eventually found her granddaughter.

On-line, I will sometimes see a reference very close to what I've done in a past job, and wonder, just for an instant, Is that me? Once upon a time, I, Gail Siegel, worked on child product safety issues! Many years ago, I, Gail Siegel, took photos of an art exhibit for the Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations in Ann Arbor! I have been to Israel. I had a boyfriend named Lonnie, in 6th grade. My daughter—whose last name is not Siegel—considered attending Evergreen, where Gail Siegel works.

But the woman out there who is married to Lonnie, or taking photographs, or living in Israel or Olympia, or working on a safety newsletter is not me. They are likely not each other, either. They are some other Gail Siegels, who very well may be living lives just a few degrees removed from my own, like a fraternal twin or fraternal quadruplets, separated at birth--or a postulated parallel universe. Or they may be some Gail Siegels with less in common with me than, say, an Ed Schwartz.

I do know a man named Ed Schwartz who convened a club of Ed Schwartzes years ago. These Ed Schwartzes all had a propensity to write letters to the editor. The potential for confusion was enormous. They get together now and then, and I’m sure they can keep each other straight in the flesh, if not in newsprint.

Indeed, at the local newspaper, I often have to deal with two John McCormicks. There is the young, crabby, John McCormick who has cursed me out in the hallway of the County Building. There is the older, jovial John McCormick, who peppers his chit-chat with jokes. I never mix them up in person, or on the phone.

But the internet—it guarantees bewilderment. Thus, it is because of you, you legions of Gail Siegels out there, that I generally remember to use my middle name (Louise) in order to keep from being confused with you. Certainly, you are kind and decent people, who do honorably by my/our name. Yet, you may prefer to be differentiated from me.

Since your names pop up from time to time, I wanted to acknowledge you, and to wish you well.

And to note this: I'm pleased that I haven't yet read any of our obituaries.

(or a shout-out to my gails...)

Dear Gail and Gail and Gail, etc:

Like you, my name is Gail Siegel.

I happen to be a writer, and every once in a while I google my name to make sure that a story has been published, or to see who is linking to my work. Inevitably, I run across one or another of you other Gail Siegels out there. I get your emails, inviting me to a golf game, or a luncheon in New York. I politely decline.

This is not a new problem. Decades ago, in college, Gail Anne Siegel’s grandmother called me one night. I knew it was a grandmother, but she didn’t sound like my grandmother. She seemed a kindly old woman, and I trust she eventually found her granddaughter.

On-line, I will sometimes see a reference very close to what I've done in a past job, and wonder, just for an instant, Is that me? Once upon a time, I, Gail Siegel, worked on child product safety issues! Many years ago, I, Gail Siegel, took photos of an art exhibit for the Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations in Ann Arbor! I have been to Israel. I had a boyfriend named Lonnie, in 6th grade. My daughter—whose last name is not Siegel—considered attending Evergreen, where Gail Siegel works.

But the woman out there who is married to Lonnie, or taking photographs, or living in Israel or Olympia, or working on a safety newsletter is not me. They are likely not each other, either. They are some other Gail Siegels, who very well may be living lives just a few degrees removed from my own, like a fraternal twin or fraternal quadruplets, separated at birth--or a postulated parallel universe. Or they may be some Gail Siegels with less in common with me than, say, an Ed Schwartz.

I do know a man named Ed Schwartz who convened a club of Ed Schwartzes years ago. These Ed Schwartzes all had a propensity to write letters to the editor. The potential for confusion was enormous. They get together now and then, and I’m sure they can keep each other straight in the flesh, if not in newsprint.

Indeed, at the local newspaper, I often have to deal with two John McCormicks. There is the young, crabby, John McCormick who has cursed me out in the hallway of the County Building. There is the older, jovial John McCormick, who peppers his chit-chat with jokes. I never mix them up in person, or on the phone.

But the internet—it guarantees bewilderment. Thus, it is because of you, you legions of Gail Siegels out there, that I generally remember to use my middle name (Louise) in order to keep from being confused with you. Certainly, you are kind and decent people, who do honorably by my/our name. Yet, you may prefer to be differentiated from me.

Since your names pop up from time to time, I wanted to acknowledge you, and to wish you well.

And to note this: I'm pleased that I haven't yet read any of our obituaries.

Tuesday, April 10, 2007

ON THE LAST DAY OF CREATION AT THE BLUE MOUNTAIN CENTER

“Which of these characters is you?” That’s what a critic or a reader—anyone who is likely not a writer him or herself—might ask the author of a piece of fiction. On occasion, one character is the writer’s voice. But my guess is that most fiction writers who are not writing veiled autobiography would answer like me: they all are.

I think about Hannah Tinti, finishing up her writing at Blue Mountain, up in the New York Adirondacks. The last night of the last day. Putting down her pen. In a zone. The story or book has reached a conclusion. An ending, if not the final end. In some ways, it’s as intended. In others, the characters have surprised her, taken on lives of their own. Said things she hadn’t expected. Refused to mumble other lines she’d turned over in her mind like jewels.

Cajoling characters isn’t as impossible as herding cats. But it’s not a military operation where everyone follows orders. Characters who come to life, who become palpable, can have wills, if not absolutely free. Like defiant children. Like all God’s children. Straying from that perfectly planned garden: its weedless beds, its mulched mounds, its cultivated rows. They climb trees, pick and hurl fruit, break down fences. They snap off the tulip tops and threaten to whip their friends with rose stems. They leave, they have sex, they fall in love, they commit atrocities, they die.

So, like a goddess—for what are writers, creators, but the gods of the page, the worlds they create. Omnipotent! At least at the start, and ceding power as their worlds gain traction and rotate. So, like a goddess, Hannah Tinti puts down her pen, be it a TUL or a Univision or a Bic. She finds her way along a path through the old growth forest. She crosses a stream--beckoned ahead by Eminem--and reaches a gathering where all the other supposed recluse writers, hermited painters and shy poets will dance. Lo, they do not rest on the final night of creation. They have been static all week, only exercising their minds. They turn up the music. They kick off their shoes. After creating worlds, they dance and they dance and they dance.

So, which of these people is holy, is God-like? The priest? The monk? The taxi driver? The prostitute? Any honest deity would have to welcome us all, without demanding an admission ticket. No repentance, no sacrifice, no good deeds, no tithing. As surely as Huck’s father belongs to Twain or Raskolnikov to Fyodor, we belong to whatever force set this wet ball in motion with a word and a kick, as surely as we writers string together, out of our own unnamed urges and curiosity, words of good and evil, words of holy and unholy intent.

“Which of these characters is you?” That’s what a critic or a reader—anyone who is likely not a writer him or herself—might ask the author of a piece of fiction. On occasion, one character is the writer’s voice. But my guess is that most fiction writers who are not writing veiled autobiography would answer like me: they all are.

I think about Hannah Tinti, finishing up her writing at Blue Mountain, up in the New York Adirondacks. The last night of the last day. Putting down her pen. In a zone. The story or book has reached a conclusion. An ending, if not the final end. In some ways, it’s as intended. In others, the characters have surprised her, taken on lives of their own. Said things she hadn’t expected. Refused to mumble other lines she’d turned over in her mind like jewels.

Cajoling characters isn’t as impossible as herding cats. But it’s not a military operation where everyone follows orders. Characters who come to life, who become palpable, can have wills, if not absolutely free. Like defiant children. Like all God’s children. Straying from that perfectly planned garden: its weedless beds, its mulched mounds, its cultivated rows. They climb trees, pick and hurl fruit, break down fences. They snap off the tulip tops and threaten to whip their friends with rose stems. They leave, they have sex, they fall in love, they commit atrocities, they die.

So, like a goddess—for what are writers, creators, but the gods of the page, the worlds they create. Omnipotent! At least at the start, and ceding power as their worlds gain traction and rotate. So, like a goddess, Hannah Tinti puts down her pen, be it a TUL or a Univision or a Bic. She finds her way along a path through the old growth forest. She crosses a stream--beckoned ahead by Eminem--and reaches a gathering where all the other supposed recluse writers, hermited painters and shy poets will dance. Lo, they do not rest on the final night of creation. They have been static all week, only exercising their minds. They turn up the music. They kick off their shoes. After creating worlds, they dance and they dance and they dance.

So, which of these people is holy, is God-like? The priest? The monk? The taxi driver? The prostitute? Any honest deity would have to welcome us all, without demanding an admission ticket. No repentance, no sacrifice, no good deeds, no tithing. As surely as Huck’s father belongs to Twain or Raskolnikov to Fyodor, we belong to whatever force set this wet ball in motion with a word and a kick, as surely as we writers string together, out of our own unnamed urges and curiosity, words of good and evil, words of holy and unholy intent.

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

GRIEVING

Kathy has told me this story before. This time, we are in a car, driving into Charleston, South Carolina. The five old college roommates, leaving Kiawah Island at the end of a long weekend. Squeezing every last minute of intimacy out of the trip.

She leans forward from the back seat so Julie, who is driving, can hear. Julie is no stranger to tragedy, awaiting her pre-teen daughter’s heart surgery, crossing her fingers the doctor will cure, not kill her. Linda, sitting beside me, has a temporary reprieve. Her ovarian cancer won’t return for four months. Caren, riding shotgun, is healthy. It’s her marriage that’s fallen apart.

Two of us are missing, too. One dead; one in a cult and only dead to the world. But we’re not thinking about them now. We’re on vacation from personal disaster while Kathy tells her tale.

It was years ago, when Kathy and her husband Gregg were camping in Alaska, in Denali National Park. One day, while hiking, other campers stopped them on the trail. Had they seen a moose? Or a bear? Kathy and Gregg hadn’t seen the moose, but kept a lookout. And then, they stumbled across the bear. He was lurking around the edges of the cul de sac where they were camped, blood staining the fur around his mouth.

They weren’t sure what had happened. Had someone said that the moose had a baby? Babies? Or was about to give birth? But what had they said about the bear?

While they debated, the moose lumbered up, bigger and more imposing than they expected. Her earth-pounding steps sent Kathy jumping into the trailer, and Gregg scurrying up the ladder to its roof. As the moose swung around her head, it seemed clear—she was on the hunt for her babes.

So began a dance, for hours. Drawn by some invisible force—the smell of blood? Anguished cries?—the moose ran at the woods, then around the circle at the end of the cul de sac. She’d head toward the grizzly’s lair, then retreat to the campsite, ears pricked up and listening, fur on her back at attention, watching and waiting, and waiting and watching.

But the rangers knew she wouldn’t find her babies alive; the bear had eaten them.

The rangers caucused, decided it was a dangerous situation. Elevated from orange to red, like a homeland security alert. Bears aren’t the only aggressive beasts, Kathy explains. Moose charge, too. Campers could get hurt.

The rangers reached into their cab for weapons. They cocked their guns, as wary of the moose as scared of the bear. The men trekked into the woods on a mission to subdue the grizzly while the moose was at the campsite. All the while, the mother moose kept her anxious vigil: scooting toward the trees, then back to the center of the clearing, eyes and ears alert, hair a-prickle.

Just a short time passed, and then the rangers lugged them out―the two dead baby moose. They threw the corpses into the back of their pickup like slabs of ruined meat while the mother moose watched. At once, her demeanor changed. Her pelt fell flat, her ears drooped. She stopped roaming and stood stock still in the center of the campsite. Motionless, for a good hour. She was frozen, expressionless.

Back in Charleston, Kathy drops her arms and rolls back her eyes, her best imitation of a stunned mother moose. We don’t laugh.

She says that’s how it went the next day, too. Kathy and Gregg woke to find the moose unmoved. In mourning. Too grief-stricken to leave the scene of the murder.

Kathy falls back in her seat. She looks around the car for a word to express the moose’s sorrow. She gives up, resorts to a phrase out of our shared past.

“Well,” she says, “that moose, she was totally bummed out.”

There are no bleak-enough words for that kind of despair.

We ride in hushed assent, staring at the maze of roadways in the distance. We can’t see the potholes and collisions that will rattle our lives in the miles ahead.

Kathy has told me this story before. This time, we are in a car, driving into Charleston, South Carolina. The five old college roommates, leaving Kiawah Island at the end of a long weekend. Squeezing every last minute of intimacy out of the trip.

She leans forward from the back seat so Julie, who is driving, can hear. Julie is no stranger to tragedy, awaiting her pre-teen daughter’s heart surgery, crossing her fingers the doctor will cure, not kill her. Linda, sitting beside me, has a temporary reprieve. Her ovarian cancer won’t return for four months. Caren, riding shotgun, is healthy. It’s her marriage that’s fallen apart.

Two of us are missing, too. One dead; one in a cult and only dead to the world. But we’re not thinking about them now. We’re on vacation from personal disaster while Kathy tells her tale.

It was years ago, when Kathy and her husband Gregg were camping in Alaska, in Denali National Park. One day, while hiking, other campers stopped them on the trail. Had they seen a moose? Or a bear? Kathy and Gregg hadn’t seen the moose, but kept a lookout. And then, they stumbled across the bear. He was lurking around the edges of the cul de sac where they were camped, blood staining the fur around his mouth.

They weren’t sure what had happened. Had someone said that the moose had a baby? Babies? Or was about to give birth? But what had they said about the bear?

While they debated, the moose lumbered up, bigger and more imposing than they expected. Her earth-pounding steps sent Kathy jumping into the trailer, and Gregg scurrying up the ladder to its roof. As the moose swung around her head, it seemed clear—she was on the hunt for her babes.

So began a dance, for hours. Drawn by some invisible force—the smell of blood? Anguished cries?—the moose ran at the woods, then around the circle at the end of the cul de sac. She’d head toward the grizzly’s lair, then retreat to the campsite, ears pricked up and listening, fur on her back at attention, watching and waiting, and waiting and watching.

But the rangers knew she wouldn’t find her babies alive; the bear had eaten them.

The rangers caucused, decided it was a dangerous situation. Elevated from orange to red, like a homeland security alert. Bears aren’t the only aggressive beasts, Kathy explains. Moose charge, too. Campers could get hurt.

The rangers reached into their cab for weapons. They cocked their guns, as wary of the moose as scared of the bear. The men trekked into the woods on a mission to subdue the grizzly while the moose was at the campsite. All the while, the mother moose kept her anxious vigil: scooting toward the trees, then back to the center of the clearing, eyes and ears alert, hair a-prickle.

Just a short time passed, and then the rangers lugged them out―the two dead baby moose. They threw the corpses into the back of their pickup like slabs of ruined meat while the mother moose watched. At once, her demeanor changed. Her pelt fell flat, her ears drooped. She stopped roaming and stood stock still in the center of the campsite. Motionless, for a good hour. She was frozen, expressionless.

Back in Charleston, Kathy drops her arms and rolls back her eyes, her best imitation of a stunned mother moose. We don’t laugh.

She says that’s how it went the next day, too. Kathy and Gregg woke to find the moose unmoved. In mourning. Too grief-stricken to leave the scene of the murder.

Kathy falls back in her seat. She looks around the car for a word to express the moose’s sorrow. She gives up, resorts to a phrase out of our shared past.

“Well,” she says, “that moose, she was totally bummed out.”

There are no bleak-enough words for that kind of despair.

We ride in hushed assent, staring at the maze of roadways in the distance. We can’t see the potholes and collisions that will rattle our lives in the miles ahead.

Sunday, May 21, 2006

WITHOUT EVA

Just weeks ago, Eva died. I always liked her, but didn’t know her well. I learned the personal details of her life incidentally and accidentally, at neighborhood gatherings.

Four years back, when her Dalmatian Prince was still alive, she threw a birthday party in her yard for the deaf old dog, complete with paper hats and cake. She invited both people and pets, but I didn’t dare bring Porter, my black lab, for fear of him humping the hostess. I don’t remember any animals save Prince and a stray cat. It was a pet-less pleasure to relax on Eva and Albert’s lawn furniture and visit.

My son was considering college then, and she warned me off of Kalamazoo, saying it ‘ruined’ her boy. He took up with the wrong crowd, and ended up modeling in New York City. Was this her code for coming out as gay? I didn’t ask. The bunch of us moved on to stories about 9/11. She and Albert both had grown children in New York, from first marriages, who’d found their spouses via cell-phone after the towers fell. Our neighbor Susan Chiaro’s father flew into Boston just as planes were grounded. Upon landing, his cabbie was weeping: the honey-mooning couple he’d dropped off that morning had boarded a doomed flight.

The usual things changed in the ensuing years. Susan moved to Madison. Prince died. I’d spy Eva power-walking when I took Porter out. Her cropped blond locks bobbed along at a brisk pace and I’d admire her lithe limbs and upbeat mood, hoping to be like her when I reached her age. Though she was but a few years ahead of me, and I kept overtaking the ages I envied, I never closed the muscular gap between her taut shape and my own softer figure.

Sometimes we’d say hello in passing, other times exchange more words. She’d mourn the lack of “a dog to pee on my flowers” and indulge Porter’s leaping greeting. Over those years, Albert began and finished an immense project in their yard, bricking in walkways, planting borders and flowers, coaxing it into a magical showpiece of a garden. Over the winters, she said he sat staring out the window, sketching and planning. Summers, he’d dig and water and prune--such work you can do without a big dog to pee on and tear up your efforts.

I passed their house at least once a day, noting the neat lemony border of petunias below their living room window, and the white grand piano behind its filmy curtains. Summer and winter, petunias or snow, a vase full of flowers, often roses, would sit atop the piano: red punctuating ivory. I never thought to ask about the piano, who might have played, whether it was Eva or Albert, or one of their children, up and gone.

Somewhere in that interval of years, we sought each other out at a neighbor’s baby shower, though our talk soon turned grim for the occasion. Eva was recently back from Poland, where her mother had died. In the hospital, when they visited, her mother’s breasts had turned black, something she’d never heard of before, nor had I.

Time advanced. Eva walked; I walked Porter. This winter, I didn’t see Eva, but didn’t wonder. There’s not much pleasure strolling hereabouts in the subzero months.

Then, in April, I heard she was dead. Diagnosed, suddenly, with gall bladder cancer. Cramps and projectile vomiting, surgery. A quick three months from discovery to death.

It’s hard to grasp an absence when someone dies who you don’t see daily. But I’ve heard a change. These days, when Porter and I pass her window at night, we’re often startled by haunting piano melodies. It’s Albert at the keys, performing concertos as lush and lovely as his garden, with Porter, the roses and me his only audience.

I never remembered to ask Eva who played piano. I know now; the music has answered.

Just weeks ago, Eva died. I always liked her, but didn’t know her well. I learned the personal details of her life incidentally and accidentally, at neighborhood gatherings.

Four years back, when her Dalmatian Prince was still alive, she threw a birthday party in her yard for the deaf old dog, complete with paper hats and cake. She invited both people and pets, but I didn’t dare bring Porter, my black lab, for fear of him humping the hostess. I don’t remember any animals save Prince and a stray cat. It was a pet-less pleasure to relax on Eva and Albert’s lawn furniture and visit.

My son was considering college then, and she warned me off of Kalamazoo, saying it ‘ruined’ her boy. He took up with the wrong crowd, and ended up modeling in New York City. Was this her code for coming out as gay? I didn’t ask. The bunch of us moved on to stories about 9/11. She and Albert both had grown children in New York, from first marriages, who’d found their spouses via cell-phone after the towers fell. Our neighbor Susan Chiaro’s father flew into Boston just as planes were grounded. Upon landing, his cabbie was weeping: the honey-mooning couple he’d dropped off that morning had boarded a doomed flight.

The usual things changed in the ensuing years. Susan moved to Madison. Prince died. I’d spy Eva power-walking when I took Porter out. Her cropped blond locks bobbed along at a brisk pace and I’d admire her lithe limbs and upbeat mood, hoping to be like her when I reached her age. Though she was but a few years ahead of me, and I kept overtaking the ages I envied, I never closed the muscular gap between her taut shape and my own softer figure.

Sometimes we’d say hello in passing, other times exchange more words. She’d mourn the lack of “a dog to pee on my flowers” and indulge Porter’s leaping greeting. Over those years, Albert began and finished an immense project in their yard, bricking in walkways, planting borders and flowers, coaxing it into a magical showpiece of a garden. Over the winters, she said he sat staring out the window, sketching and planning. Summers, he’d dig and water and prune--such work you can do without a big dog to pee on and tear up your efforts.

I passed their house at least once a day, noting the neat lemony border of petunias below their living room window, and the white grand piano behind its filmy curtains. Summer and winter, petunias or snow, a vase full of flowers, often roses, would sit atop the piano: red punctuating ivory. I never thought to ask about the piano, who might have played, whether it was Eva or Albert, or one of their children, up and gone.

Somewhere in that interval of years, we sought each other out at a neighbor’s baby shower, though our talk soon turned grim for the occasion. Eva was recently back from Poland, where her mother had died. In the hospital, when they visited, her mother’s breasts had turned black, something she’d never heard of before, nor had I.

Time advanced. Eva walked; I walked Porter. This winter, I didn’t see Eva, but didn’t wonder. There’s not much pleasure strolling hereabouts in the subzero months.

Then, in April, I heard she was dead. Diagnosed, suddenly, with gall bladder cancer. Cramps and projectile vomiting, surgery. A quick three months from discovery to death.

It’s hard to grasp an absence when someone dies who you don’t see daily. But I’ve heard a change. These days, when Porter and I pass her window at night, we’re often startled by haunting piano melodies. It’s Albert at the keys, performing concertos as lush and lovely as his garden, with Porter, the roses and me his only audience.

I never remembered to ask Eva who played piano. I know now; the music has answered.

Thursday, December 29, 2005

MARSHALL FIELD'S OTHER WINDOWS

Marshall Field’s, the Chicago department store about to lose its name to Macy’s, has long been known for its windows. Each year, the ground floor display windows fill with elaborate winter scenes: leaping nutcrackers, Santas and elves, princes, skaters and ballroom dancers. They glitter, shine and mesmerize shoppers on pilgrimages from Decatur to Indianapolis.

This is a tale of Field’s other windows.

The ground floor of Field’s flagship State Street store is a several story high atrium, stretching above the rooms in curlicued plaster. When my father was a young college student working as a stock boy at Marshall Field and Company, his job included opening the windows. Another young man, a student like him, trained him to do it.

My father would stand on a narrow catwalk and push the windows open one by one. When he recounts this episode, he gestures outward with his arms. I can’t tell if he used bare hands or poked them out with a pole.

Then, he decided he wanted a day off. He can’t remember why. A summer day? A ball game? My father lived for baseball as a youth, his one heartache: his own father refusing to sign a farm league contract with the Cubs because my father was too young.

On that obscure day off, the day my father didn’t work, the other young man took his place—creeping along the catwalk, pushing open the windows. On that day, the day my father didn’t work, the other boy pressed the windows wide, leaned forward and fell. He plunged to his death.

Fifty-eight years later my father remembers the young man’s funeral. My father didn’t introduce himself to the parents, didn’t say it should have been him, that he should have been working that day.

He tells this story at the holiday table, on the eve of Field’s own demise. It’s a grim tale and I forget to ask if he ever did it again, ever returned to work, ever crawled along the catwalk, poking out the windows, ever whispered to his coworkers of that lost young man. For whatever he did, he did it safely enough to quadruple his years, to bring me into this world and to make me mourn and remember a nameless young man I never have met.

Sunday, November 20, 2005

STANLEY ELKIN'S MAGIC

Mom and Dad and Dianne Schramm are in a car with Stanley Elkin around 71st Street on the south side of Chicago. It's a busy area back in the 1940’s. While someone is in a store, Stanley decides to try to hypnotize Dianne. He moves his finger back and forth, and she follows it with her eyes. She goes under. It's the first time he's successful with hypnosis.

Okay, he says. Now I am going to bring you out, he says.

He snaps his fingers. Nothing.

He claps his hands. Nothing. She won't come to.

He tries every trick he knows to reverse the spell. Still, nothing works. She's under.

She sleeps, does Dianne Schramm, whose picture I will find in my parents' photo album decades later. After Korea. Who will marry Morty Haberman, who will divorce him, a man now dying of esophageal cancer.

All these years later, after Dianne's trance, my parents will still know Morty. They will spend New Year's Eve 2004 with him, watch as he chugs morphine before each bite of food to kill the pain.

But she, Dianne, can't read that future, or the titles of Stanley’s future books, or his Multiple Sclerosis and death, or Morty’s doomed esophagus, or at least says nothing about them. Instead, she sleeps, oblivious to Stanley's imprecations, his attempt to bring her back to that present, before my past even begins.

She sleeps a long while, waking with a headache in her own time, says nothing about what time, what future or present she's glimpsed, and whether it's fate that's given her a headache, or Stanley and his clumsy, novice technique.

I don't know if he ever hypnotized anyone again, at least without a pen.

Mom and Dad and Dianne Schramm are in a car with Stanley Elkin around 71st Street on the south side of Chicago. It's a busy area back in the 1940’s. While someone is in a store, Stanley decides to try to hypnotize Dianne. He moves his finger back and forth, and she follows it with her eyes. She goes under. It's the first time he's successful with hypnosis.

Okay, he says. Now I am going to bring you out, he says.

He snaps his fingers. Nothing.

He claps his hands. Nothing. She won't come to.

He tries every trick he knows to reverse the spell. Still, nothing works. She's under.

She sleeps, does Dianne Schramm, whose picture I will find in my parents' photo album decades later. After Korea. Who will marry Morty Haberman, who will divorce him, a man now dying of esophageal cancer.

All these years later, after Dianne's trance, my parents will still know Morty. They will spend New Year's Eve 2004 with him, watch as he chugs morphine before each bite of food to kill the pain.

But she, Dianne, can't read that future, or the titles of Stanley’s future books, or his Multiple Sclerosis and death, or Morty’s doomed esophagus, or at least says nothing about them. Instead, she sleeps, oblivious to Stanley's imprecations, his attempt to bring her back to that present, before my past even begins.

She sleeps a long while, waking with a headache in her own time, says nothing about what time, what future or present she's glimpsed, and whether it's fate that's given her a headache, or Stanley and his clumsy, novice technique.

I don't know if he ever hypnotized anyone again, at least without a pen.

Friday, November 19, 2004

THE MEETING

The department secretary chews on her cheek.

The warehouse manager leans into her elbow on the table, chin resting in hand, and digs her nails into her face.

The deputy clerk squeezes his mouth with his fingers, smoothes down the hair on the back of his hand.

The purchasing director is biting her lip, touching her painted face with enameled fingertips, picking stray polish off her flesh.

The chubby lawyer rubs his ruddy face, then tugs at his beard.

The deputy director nods, smiles and blinks.

From time to time her tongue darts from her mouth, moistens her lips, and slowly retracts. It has a will of its own, triggered by dry spells or perhaps passing flies.

The law student recovering from a concussion rests his forehead in his hands.

The IT director props her chin in her palm, tenderly nipping at her nails. The outreach director pokes her pen in her mouth, then uses it to dig in and clean out her ears.

The PR assistant raises her eyebrows, plays with an earring, furrows her brow, scratches the bridge of her nose with a fist.

The elected official strokes his moustache and smirks.

The meeting concludes; the next date is set. Relief lights their faces and all rise and stretch.

The department secretary chews on her cheek.

The warehouse manager leans into her elbow on the table, chin resting in hand, and digs her nails into her face.

The deputy clerk squeezes his mouth with his fingers, smoothes down the hair on the back of his hand.

The purchasing director is biting her lip, touching her painted face with enameled fingertips, picking stray polish off her flesh.

The chubby lawyer rubs his ruddy face, then tugs at his beard.

The deputy director nods, smiles and blinks.

From time to time her tongue darts from her mouth, moistens her lips, and slowly retracts. It has a will of its own, triggered by dry spells or perhaps passing flies.

The law student recovering from a concussion rests his forehead in his hands.

The IT director props her chin in her palm, tenderly nipping at her nails. The outreach director pokes her pen in her mouth, then uses it to dig in and clean out her ears.

The PR assistant raises her eyebrows, plays with an earring, furrows her brow, scratches the bridge of her nose with a fist.

The elected official strokes his moustache and smirks.

The meeting concludes; the next date is set. Relief lights their faces and all rise and stretch.

Friday, July 09, 2004

DREAD

Dread. It's become ubiquitous. Although tomorrow is my birthday, it's not dread of getting older. Rather, dread of pain, of loss, of suffering, of random attack, of war.

Dread is overriding, the modern American posture. An attitude. Dread takes off, takes over, pursues from behind. Dread stalks, like the mugger waiting in the shadows, the terrorist on the train platform with a bomb in his backpack.

In our collective imaginations we are only moments from running, from racing away from the thief, the plastique, the shrapnel, the fire, the chemicals -- three hundred million variations on the young Vietnamese girl in the photograph. She is fleeing, arms flailing, mouth wide in a silent scream.

Dread is the post-millennial soundtrack; we are dancing to its tune like drunks in a bar, a bully shooting bullets at our feet.

Dread. It's become ubiquitous. Although tomorrow is my birthday, it's not dread of getting older. Rather, dread of pain, of loss, of suffering, of random attack, of war.

Dread is overriding, the modern American posture. An attitude. Dread takes off, takes over, pursues from behind. Dread stalks, like the mugger waiting in the shadows, the terrorist on the train platform with a bomb in his backpack.

In our collective imaginations we are only moments from running, from racing away from the thief, the plastique, the shrapnel, the fire, the chemicals -- three hundred million variations on the young Vietnamese girl in the photograph. She is fleeing, arms flailing, mouth wide in a silent scream.

Dread is the post-millennial soundtrack; we are dancing to its tune like drunks in a bar, a bully shooting bullets at our feet.

Monday, July 05, 2004

THE RICK MOODY ARGUMENT